La comunità ebraica di Brindisi

Via Giudea, in ricordo del quartiere ebraico (sec. VIII – XVI)

Memoria del quartiere ebraico che si sviluppò a Brindisi tra l’VIII sec. e il XVI sec. è via Giudea, che nel 1939, a seguito delle leggi razziali, fu denominata via Tunisi, per poi tornare in tempi recenti ad assumere il nome che per secoli aveva mantenuto la memoria del quartiere ebraico (il ghetto, che per la prima volta venne realizzato a Venezia nel 1516, poi istituito da Papa Paolo IV nel 1555, è imposto e perimetrato dall’Autorità, mentre il quartiere è insediamento su base volontaria).

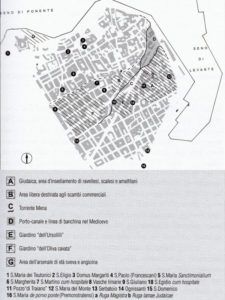

La conformazione del porto di Brindisi in età antica comprendeva un porto-canale navigabile di cui parlò anche Strabone, un terzo piccolo seno in corrispondenza di dove oggi è la parte terminale di corso Garibaldi, anticamente la mena (mena, da menare, gettare, buttare), per la presenza di un torrente che nasceva all’incirca in corrispondenza di Via Schena e in cui confluivano anche le acque reflue (fig. 1). La disponibilità di acqua e la navigabilità del porto-canale avevano favorito le attività preminenti della comunità ebraica, che era soprattutto dedita alla concia e alla tintura dei pellami, oltre a quella classica del prestito di denaro. L’areale di via Giudea si estendeva sino al Belvedere sul Monte, a via Pergola, a via Amena. Via Giudea – anticamente Ruga Lame Judayce, da un documento del 1320 citato dal Vacca – era il fulcro del quartiere e qui forse era la sinagoga, probabilmente laddove era la chiesa di S. Simone dei giudei, citata, a dire del Vacca, in un documento del ‘500, chiesa che era già in rovina nel 1565 e di cui non è rimasta traccia. Certamente un documento notarile attesta la presenza di una scuola ebraica, che generalmente era all’interno della sinagoga o attigua ad essa (N. Vacca).

Alla fine del VII sec. il clima di Brindisi era buono, come dimostrava l’aspetto florido degli abitanti e il loro temperamento sano, gagliardo, vivace, spiritoso e capace di apprendere (A. Della Monaca). Vi erano però grandi piogge estive che creavano stagni, situazione aggravata dalla presenza dal porto-canale. Fu Ferdinando IV di Borbone a far eliminare il canale in cui scorrevano, e spesso s’impantanavano, le acque di rifiuto delle abitazioni e dei laboratori di tintoria e conceria che si trovavano in via Giudea, unite a quelle piovane, che ammorbavano l’aria soprattutto in estate. Nel 1797 il canale-palude fu tombato e divenne la strada Carolina, per poi essere intitolata a Garibaldi nel 1882.

Quella della comunità ebraica a Brindisi è una storia di alterne vicende, in quanto la disponibilità economica favoriva il prestito, spesso con interessi da usura anche sino al 45%, altre volte faceva da calmiere degli interessi praticati dai banchieri fiorentini e genovesi. Per questo le genti ebraiche furono accolte e benvolute, ma scacciate con pretesti religiosi quando dovevano essere restituiti i denari. Tuttavia, quando ci furono le condizioni favorevoli, la comunità ebraica a Brindisi coltivò le scienze, le lettere e le arti liberali (P. Camassa), portando vantaggio alla città.

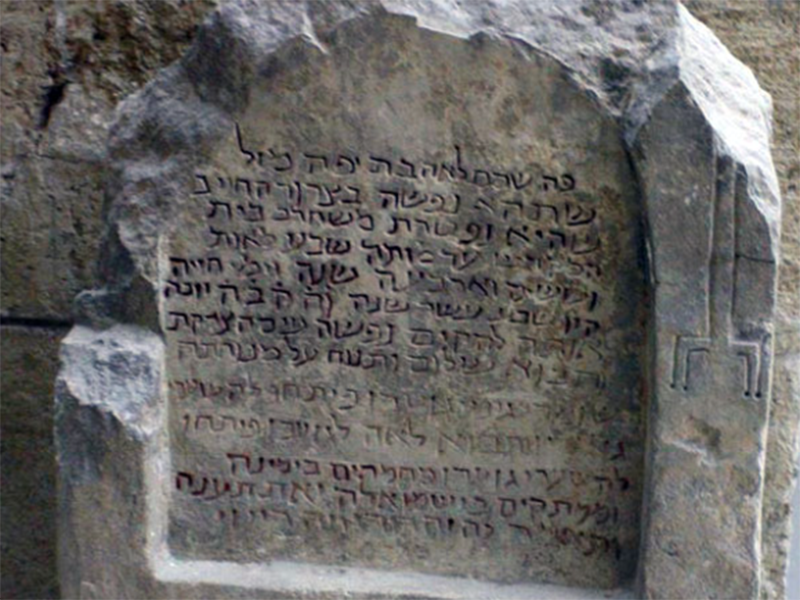

All’estremo limite del Seno di Ponente gli israeliti avevano una fonte, detta dell’acqua ebrea (P. Camassa), da cui si rifornivano per le loro necessità, mentre separato dal quartiere ebraico fu il luogo di sepoltura della comunità, che era in località Tor Pisana (scheda n. 26), dove sul finire del XIX sec. l’arcidiacono Tarantini ritrovò alcune iscrizioni ebraiche. Tra queste notevole è quella dedicata alla fanciulla Lea, di 17 anni, del IX sec., conservata presso il Museo Archeologico “F. Ribezzo” di Brindisi (fig. 2).

Note Bibliografiche:

– Alberto Del Sordo, Toponomastica brindisina, il centro storico, Schena ed., Fasano (Br) 1990

– Rosanna Alaggio, Il Medioevo nelle città italiane – Brindisi, Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, Spoleto, 2015

– Nicola Vacca, Brindisi ignorata, ed. Vecchi & C., Trani (BA), 1954

– Pasquale Camassa, Gli Ebrei a Brindisi (fascicolo di 4 pagine, Tip. Del Commercio, Brindisi 1934)

The Jewish community of Brindisi

Via Giudea, in memory of the Jewish district (VIII – XVI century).

Via Giudea preserves the memory of the Jewish district, developed in Brindisi between the VIII and the XVI century. In the aftermath of the racial laws, it was renamed via Tunisi, but in recent times it turned back to its previous name, which have preserved the memory of the Jewish district for centuries. Differently from the Ghetto, firstly created in Venice in 1516 and then introduced in 1555 by Pope Paul IV, which is imposed and bounded by public authorities, the district is a settlement on voluntary basis.

The shape of the port of Brindisi in the ancient age included a navigable dock-canal. It was also called “mena” (from the Latin word menare, meaning to throw, to waste) due to the presence of a stream which originated in correspondence of via Schiena, and where wastewater flowed. The dock-canal was also mentioned by Strabone, who described it as a third “seno”, in correspondence to what today is the end of Corso Garibaldi. The availability of water and the navigability of the dock-canal fostered the main activities of the Jewish community, dedicated to the tanning and dyeing of leather, a part from the classic activity of the lending of money. The range of via Giudea was extended until Belvedere sul Monte, via Pergola, and via Amena. Via Giudea, previously known as Ruga Lame Judayce (on the basis of a document dated back to 1320, cited by Vacca), was the core of the district and it is likely that here there was the synagogue, where there was the synagogue of S. Simone of Jewish people. This church is cited by a document dated back to the ‘500, as Vacca says, but it was already in ruins in 1565, and today there is no evidence left of it. What is beyond dispute is that there was a Jewish school, as attested by a notarial deed, which generally was located inside a synagogue or near to it (N. Vacca).

At the end of the VII century the climate of the city was good, as demonstrated by the flourishing appearance of its inhabitants and by their healthy, vigorous, lively, witty and able to learn temper (A. Della Monaca). Nonetheless, there were heavy summer rains which used to create ponds, a situation compounded by the presence of the dock-canal. Ferdinand IV of Bourbon decided to eliminate the canal where the wastewater flowed together with rainwater, and which usually got bogged down and polluted the air, especially in summertime. These wastewaters came from dwellings, and from dyeing and tannery workshops located in via Giudea. In 1797 the canal-dock was covered and became Carolina Road, then entitled to Garibaldi in 1882.

That of the Jewish community in Brindisi is a story of ups and downs. This is because the financial means sometimes fostered the lending activity, often with interest rates up to 45%, and other times represented a price cap to interests applied by Florentine and Genoese bankers. For this reason, Jewish people were hailed and welcomed, but then expelled when the money had to be returned back. On the other hand. When the condition were favorable, Jewish people in Brindisi cultivated sciences, arts and liberal arts, (P. Camassa) benefiting the city.

At the extreme limit of the Seno di Ponente, Israelites had a source of water, so-called “Jewish water (P. Camassa), from where they supplied water for their necessity. Separated from the district there was the burial place of the community, in the site “tor Pisana” (factsheet n. 26). There, at the end of XIX century, the archdeacon Tarantini found some Jewish inscriptions. Among them there is a remarkable one, dedicated to the girl Lea, 17 years old, from the IX century. Today it is kept at the Archeologic Museum “F. Ribezzo” of Brindisi (fig. 2)

Bibliographic notes:

– Alberto Del Sordo, Toponomastica brindisina, il centro storico, Schena ed., Fasano (Br) 1990

– Rosanna Alaggio, Il Medioevo nelle città italiane – Brindisi, Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, Spoleto, 2015

– Nicola Vacca, Brindisi ignorata, ed. Vecchi & C., Trani (BA), 1954

– Pasquale Camassa, Gli Ebrei a Brindisi (fascicolo di 4 pagine, Tip. Del Commercio, Brindisi 1934)