L’Anfora di Brindisi

Area archeologica di Apani.

Con una lettera del 6 dicembre 1881, l’arcidiacono brindisino Giovanni Tarantini, incaricato dal Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione di svolgere il ruolo di Ispettore degli scavi e dei monumenti di Brindisi, informava lo storico Theodor Mommsen, considerato il più grande classicista del XIX secolo, del ritrovamento di strutture e reperti riferibili ad un insediamento artigianale nella località di Apani, anticamente Lapani, proprietà che, con la masseria di Lapani del XVI sec., dal 1678 apparteneva alla famiglia Granafei di Mesagne. Nel sito lo stesso Tarantini evidenziava la presenza di cave di ottima argilla. Il testo venne pubblicato nel IX volume del CIL sotto la denominazione Amphorae Calabrae ed è conservato presso la Biblioteca arcivescovile “A. De Leo” a Brindisi.

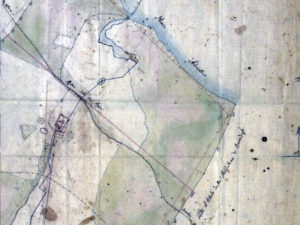

L’area è attraversata dal canale Apani, che nasce in località Marmorelle e che, con i lavori di bonifica eseguiti dall’Ente Irrigazione negli anni ’50 circa, ha perso la sua foce naturale in località Posticeddu per opere di deviazione nel tratto terminale. Nello stesso periodo, per via della Riforma fondiaria, le terre vennero espropriate e frazionate in unità produttive per lo sfruttamento agricolo. Parallelamente alla linea di costa, inoltre, dalle antiche planimetrie della Masseria di Lapani (fig. 1), è segnalata la Via Traiana, erroneamente designata Appia, di cui permangono tracce di un antico viadotto di superamento del corso fluviale (fig. 2).

Intorno al 1960 l’archeologa americana E. Lyding Will, sulla base della pubblicazione degli scritti del Tarantini nel CIL e di perlustrazioni in loco, giunse all’identificazione del sito. Successivamente, grazie a campagne di scavo eseguite, a partire dal 1964, dalla Soprintendenza Archeologica della Puglia e condotte in primis da Benita Sciarra, poi da N. Cuomo Di Caprio, è stato rinvenuto un importante insediamento artigianale di produzione di oggetti ceramici, con presenza di numerosissimi cocci, di anfore anche integre e di due distinte fornaci, la prima a poche centinaia di metri dal litorale, laddove già il Tarantini aveva segnalato le cave di argilla ottima per la fabbricazione di vasi. Benita Sciarra pubblicò i risultati delle indagini unitamente ad una prima edizione di un repertorio morfologico ed epigrafico delle anfore di Apani, prodotte indicativamente tra la seconda metà del II sec. a.C. e la metà del secolo successivo.

In seguito si sviluppò un interesse crescente per lo studio delle anfore commerciali di età romana provenienti dal contesto produttivo brindisino, a partire dalla stessa archeologa americana E. Lyding Will, che riconobbe da subito nelle anfore olearie brindisine il contenitore più diffuso, tra quelli importati di provenienza italica, nei mercati orientali dell’Egeo e dell’Egitto durante il I sec. a.C., mentre lo studioso di storia commerciale antica A. Tchernia individuò e riconobbe il contenitore brindisino tra i materiali che costituivano il carico di una nave oneraria affondata al largo di Marsiglia.

La Will, ancora, affrontò il problema della definizione tipologica dell’Anfora di Brindisi, caratterizzata dal corpo globulare terminante con piccolo puntale sagomato a bottone, collo basso con orlo ad anello, sotto cui si impostano le due anse a sezione circolare a quarto di cerchio, spesso bollate, e attribuì il contenitore brindisino prodotto ad Apani al tipo 11a della classificazione da lei elaborata sulla base del materiale anforario rinvenuto nei mercati orientali ed in particolare nell’Agora di Atene. Altri studiosi, tra i quali P. Baldacci, hanno ipotizzato una rete di scambi tra l’Apulia e l’Italia settentrionale a partire da contenitori documentati nella Cisalpina, il cui repertorio morfologico ed epigrafico mostra affinità con le anfore di Brindisi.

L’archeologa brindisina Paola Palazzo, in seguitò, dedicò la sua tesi di laurea alle anfore di Apani (fig. 3), restituendo e pubblicando un articolato impianto tipologico ed epigrafico dell’imponente mole di reperti affioranti nel sito di Apani. Ci dice la Palazzo che la distribuzione di materiale su di una superficie così estesa fa presupporre le vaste dimensioni e l’articolata organizzazione del complesso artigianale brindisino, strategicamente sorto su di un sito eccezionalmente adatto per conformazione geografica all’impianto di officine ceramiche, ma anche predisposto ai commerci per il naturale approdo e per la disponibilità di collegamenti marini, fluviali e terrestri, mentre l’eccezionale quantità di reperti rinvenuti testimonia la presenza di ulteriori impianti produttivi, fornaci da ricercare nei dintorni, a partire da dove è maggiore la presenza di cocci.

Note bibliografiche:

– Paola Palazzo, Le anfore di Apani (Brindisi), Scienza e Lettere ed., Roma, 2013

The amphora of Brindisi

Apani’s archeological area, Roman viaduct and furnaces.

Brindisi’s archdeacon Giovanni Tarantini was appointed by the Ministry of the Public Education as inspector of the excavations and monuments of Brindisi. By a letter dated 6th of December 1881, he informed Th. Mommsen of the discovery of structures and findings related to a handcraft settlement in the site of Apani. The location, previously called “Lapani”, together with Lapani farm (XVI century) belonged to Granafei family, from Mesagne, since 1678. Tarantini highlighted the presence of quarries of excellent clay. The text was published in the IX volume of CIL, under the name of Amphorae Calabrae, and is still cherished in the archiepiscopal library “A. De Leo”, in Brindisi.

The area is crossed by the Apani Canal, which rises in Marmorelle site. The Canal lost his natural mouth in “Posticieddu”, due to land reclamation works undertaken by the Irrigation authority in the Fifties’, which diverted the Canal. In the same period, due to the land reform, lands were expropriated and divided into productive units for agriculture use. In addition, planimetries of the Lapani farm marked the presence of an ancient viaduct to overcome the river, of which there still are traces. It was located in “via Trajana”, erroneously called “via Appia”, a street parallel to the coastline.

Around 1960, American archaeologist E. Lyding Will identified the site, on the basis of Tarantini’s texts published in the CIL, and also thanks to on-site investigations. Since 1964 excavations works were executed by Puglia Archaeological Superintendence and conducted by Benita Sciarra, first, and by N. Cuomo di Caprio, then. They allowed to discover an important handcraft settlement for the production of ceramic objects, as shown by the findings of shards, amphoras and two furnaces. The first of these was found just a few hundred meters from the coast, where Tarantini had already highlighted the presence of quarries of excellent clay for the manufacture of vases. Benita Sciarra published the results of her investigation together with the first edition of “Apani’s amphoras morphological and epigraphic repertoire”, indicatively produced between the first half of the II century B.C. and the half of the next century.

Later, the interest for Roman commercial amphoras found in Brindisi raised. The archaeologist E. Lyding Will recognised that olive oil amphoras from Brindisi were the most used Italian container in eastern markets, those of the Aegean Sea and Egypt, in the I century B.C. At the same time, A. Tchernia, scholar of ancient history, identified Brindisi’s amphoras among the loading of a merchant ship sank off the coast of Marseille.

Furthermore, Will faced the problem of the typological classification of the amphora of Brindisi. It is characterized by: a globular body ending with a small tip contoured by buttons; ring-edged low neck, beneath which there are the two handles; these have a circular section with a quarter circle, usually labeled. Will ascribed the container of Brindisi to category “11a” of her classification of amphoras equipment, based on the findings of Eastern markets, in particular that of the Athenian Agora. Other scholars, namely P. Baldacci, suggested the existence of a network of trade between Apulia and Northern Italy. His hypothesis is based on the comparison of the containers from Cisalpina with the amphoras of Brindisi, which shows similarities among these two morphologic and epigraphic repertoires.

Later, the archaeologist Paola Palazzo, from Brindisi, analysed the amphoras of Apani in her bachelor’s thesis. She finally published an articulated typological and epigraphic list on the impressive mass of finds in Apani site. Palazzo claims that the dissemination of finds on a such extended area suggests the big size and the articulated organization of the Brindisi’s handcraft settlement. The settlement was strategically located on an area suitable for the installation of ceramic workshop, thanks to its geographical conformation. Moreover, the area was suitable for trade, due to the presence of a natural harbor and the availability of sea, river and land connections. At the same time, the impressive mass of artefacts found in the area indicates the presence of further production plants, to be searched for in the site where there are more shards.

Bibliographic notes:

– Paola Palazzo, Le anfore di Apani (Brindisi), Scienza e Lettere ed., Roma, 2013